Dr. Lindsay Oberman discusses this in depth. The original link is as follows: https://achievetms.com/dorsolateral-prefrontal-cortex-is-everyones-favorite-region-to-stimulate-why/

In brief, as a summary this is some of what she has discussed–

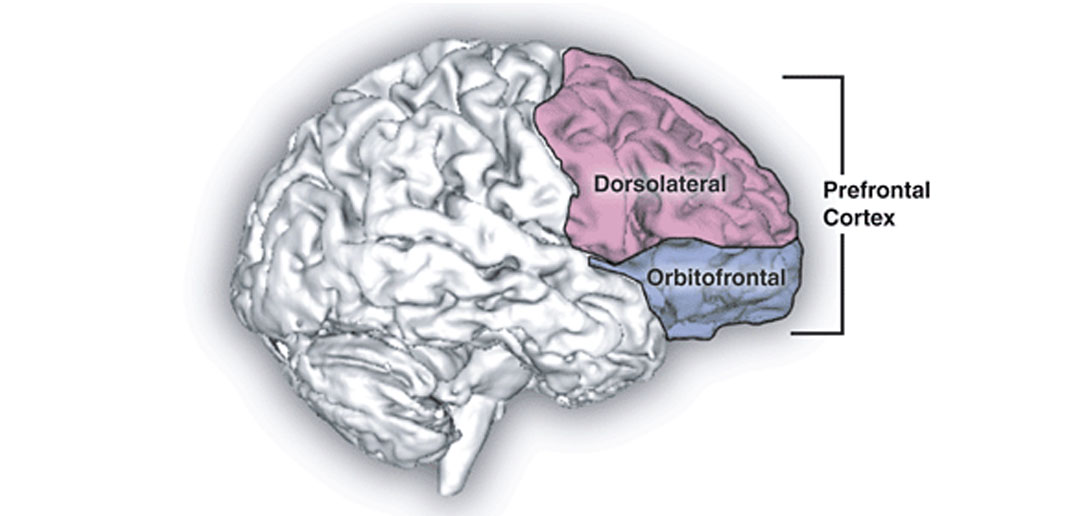

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has shown promise in the treatment of anxiety, addictions, autism spectrum disorders, and depression to name a few. But why is one particular area of the brain of such particular interest? Aren’t these all different disease processes? Are we focusing on the DLPFC simply because it is the most heavily researched (and stimulating other areas and result in equivocal results)? Or is there something special about the pathophysiology of the DLPFC?

In particular, for depression, there is undoubtedly a strong link between the DLPFC and treatments for depression. The left DLPFC has been found to be underactive in depressed patients and this region of the brain has deep connections to other areas heavily involved in mood regulation including the insula, anterior cingulate, and amygdala. Evidence based psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy and TMS increase activity in this area of the brain and promote therapeutic connections it has with these limbic structures. The benefits of TMS for depression have been replicated large clinical trials. Not one, not two, or three, but many studies. In particular, high frequency TMS. As more research is done, people are trying to fine tune this further as the dorsomedial and ventromedial prefrontal cortices are connected with subcortical reward circuits and limbic structures and show promise as TMS targets. However, the research supporting these targets is not yet as robust in volume as the DLPFC which is why insurance is currently not reimbursing for these other targets…yet.

Another attractive feature of the DLPFC is the connectivity it has with the parietal, deeper subcortical structures, and prefrontal regions of the brain. The DLPFC is also very involved in reward processing and cognition. The DLPFC also encompasses a decent volume of the brain and is involved in executive function, working memory, and spatial attention. This makes the area an attractive target for addictions, thought disorders (e.g. schizophrenia), and neurocognitive disorders (e.g. dementia). Of note, so far in the literature, TMS does not seem to improve these skills in individuals who do not have a disorder.

At the end of the day, just like any medical treatment, TMS only still works for the right candidate, for the right disorder, in the right target. It is not meant to be a cure all. In addition, many studies have what is known as a “sham” or placebo group. In every trial, there is some degree of placebo effect and this is not specific to mental health. There is something inherently therapeutic about getting up, getting dressed, having that social interaction and feeling validated that does promote therapeutic effects in our neurophysiology as well. But the research even when placebo controlled shows that there is something additionally therapeutic about stimulating the DLPFC and other promising targets as well.